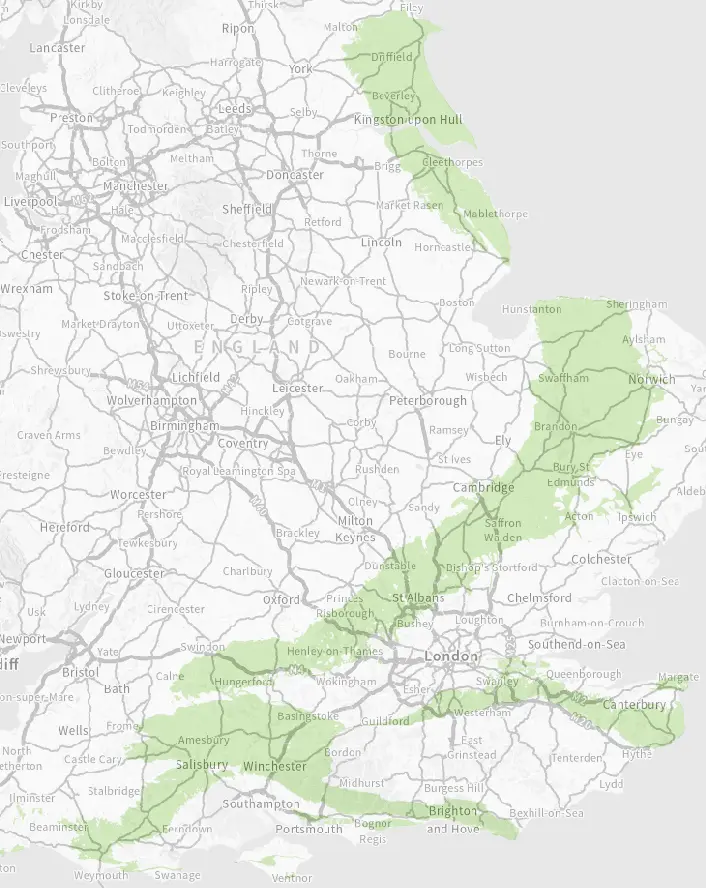

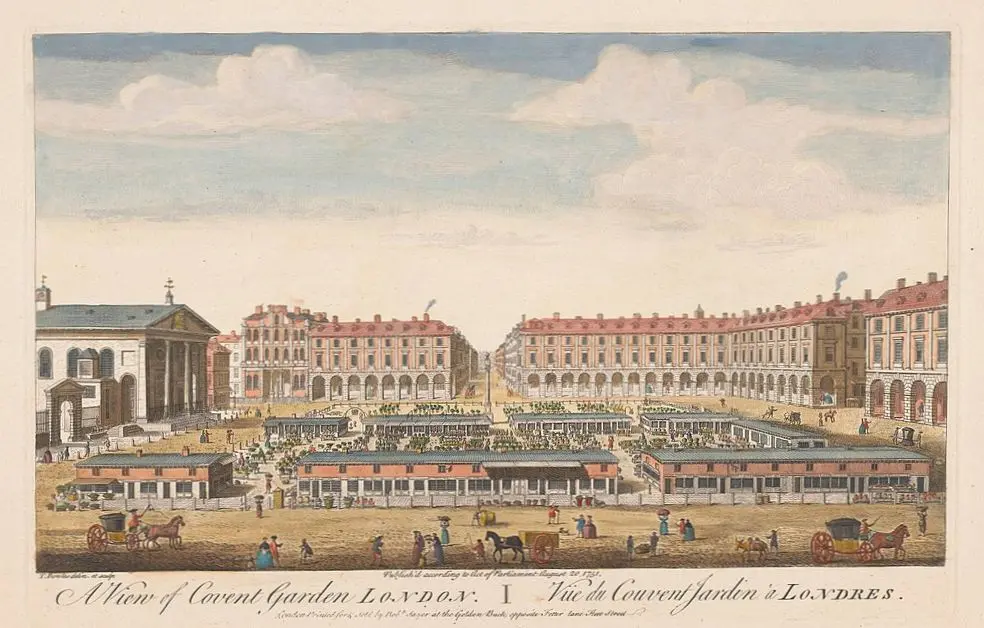

Many people are surprised to learn that truffles can be found growing wild in England. This is not a recent discovery; from the late 17th century until the 1930s, truffle hunting was a cottage industry with the main centres in Wiltshire, Sussex and Hampshire. The Wiltshire hunters travelled far and wide to Dorset, Hampshire, Sussex, Kent, Buckinghamshire, Oxfordshire and Berkshire (1) and Somerset, Herefordshire, Surrey, and the Isle of Wight (2). There may have also been professional truffle hunters in the Midlands and Northern counties. Gamekeepers and gardeners on some estates knew how to find them and truffles had been discovered as far north as Durham and Cumberland (now part of Cumbria), but they were most sought in the south. Those involved were often farm labourers, woodsmen or shepherds, who turned to truffle hunting in the autumn and winter. With their dogs, they searched beech woods for truffles to sell direct to customers and to middlemen who sold them at Covent Garden in London. Some also provided entertainment for the gentry and their country estate guests. For a variety of reasons, the “last professional truffle hunter” retired in the 1930s, his knowledge going to the grave with him. Starting in about the year 2000, there was a rebirth of the industry and its growth has continued to the present day. In this article, we look at this history with particular reference to Wiltshire, Sussex and Hampshire, the reasons why truffle hunting almost died out in England, and finally, at the re-birth of the English truffle industry. In others, we look at some classic ways that truffles were served in the 18th and 19th centuries and the history of the study of British truffles.

Earliest Description

The earliest known description of truffles in England was in 1693 by the Physician and Naturalist Tancred Robinson. In one of his papers for The Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions, he gives “An account of the tubera terræ, or truffles found at Rushton in Northamptonshire; with some remarks thereon”. He wrote:

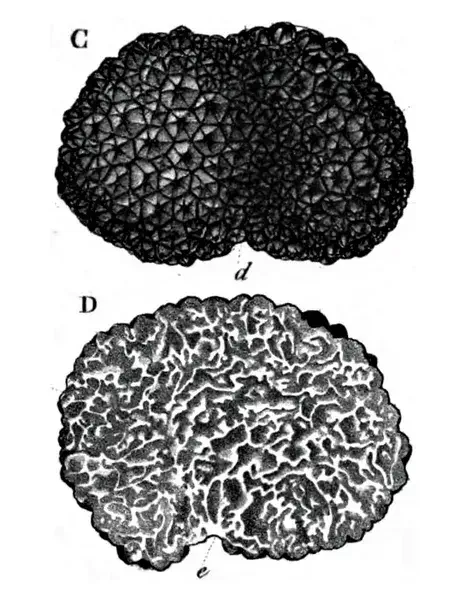

The Tubera Terræ (which you was pleas’d to send me, together with a Draught of them drawn with your own Pencil) observ’d lately at Rushton in Northamptonshire, by that curious and learned Gentleman Mr. Hatton, are indeed the true French Truffles, the Italian Tartuffi or Tartuffole, and the Spanish Turmas de Tiera, which are noted by Mr Ray to be found in our British Soyl [sic]. Those observed in England are all included in a studded Bark or Coat; the Tubercules resembling the Capsules or Seed–Vessels of some Mallows and Aloeas the inward substance is of the consistence of the fleshy part in a young chestnut, of a paste colour, of a rank or hircine odour, and unsavoury, streaked with many white Veins or threads, as in some Animals’ Testicles; the whole is of a globose figure, though unequal and chunky. (3)

What was being described was the Common Truffle (Tuber cibarium), now called the summer truffle (Tuber aestivum) / autumn truffle (Tuber uncinatum). Their season begins in July or August and lasts till January or February.

Where are Truffles Found?

One of the early mycologists, CE Broome, was particularly interested in truffles. He searched the woods enthusiastically for them in the middle of the last century.

Some trees appear to be more favourable to the production of truffles than others. I have generally found Tuber aestivum under beech trees but also under hazel. (4)

We would agree that beech is the best tree type for truffles, but would add oak, hazel, birch, holly and hornbeam to this list. As well as the right trees, the right soils are required:

The districts of England especially suited to produce truffles would thus appear to be situated on the great band of calcareous beds which run diagonally across the island from the south-eastern corner of Devonshire to the mouth of the Wash in Norfolk, occupying all the country that lies to the south-east of such a line, including the counties of Somerset, Dorset, Wiltshire, Gloucester, Hampshire, Berkshire, Kent, Hertfordshire, and parts of Northampton, Norfolk, and Lincoln. (4)

Thus, it was the chalk downs where they were mainly found – “…especially where plantations of beech flourish, and in many gentlemen’s parks, and on lawns”. (5). “Gentlemen’s parks” (country estates) were ideal for truffles with many trees being planted – “pleasure-grounds”, avenues, preserves, shrubberies, shelterbelts and clumps. This was part of the “English Landscape Style” – naturalistic parkland with trees, expanses of water and smoothly rolling grass, created under landscape architects such as Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown and his successor Humphry Repton.

At this time, landowners became obsessed with sport, particularly fox-hunting and shooting game birds (6). Truffle hunting became another sport for the gentry, with truffles known from many country estates on the chalk.

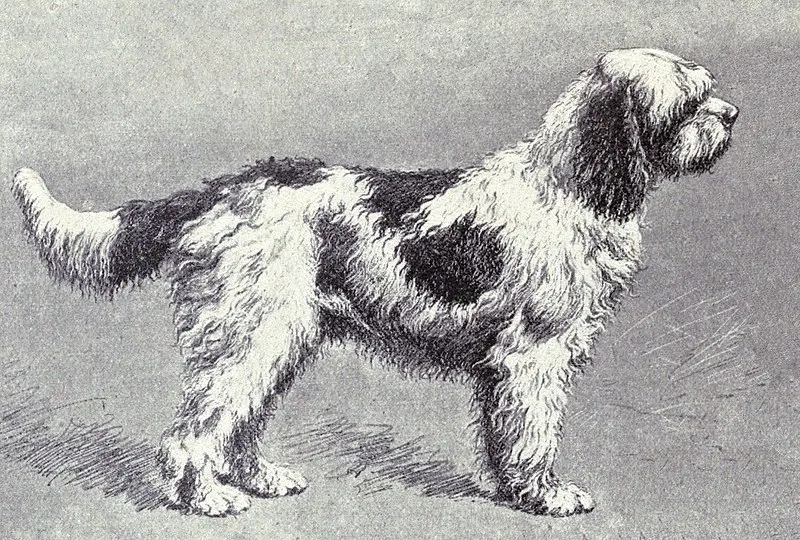

Truffle Dogs

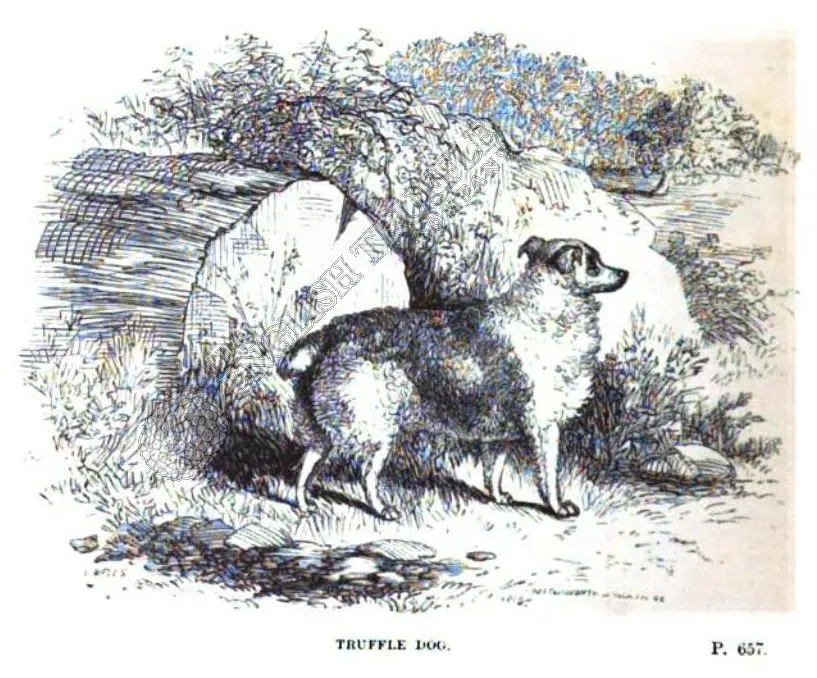

Most people think of pigs as the animal used for truffle hunting. They have been used occasionally in France, Italy, Germany and indeed England, but are not as docile as dogs and are very keen to eat any truffles they find. Dogs have been used by most truffle hunters, however, there are reports of men and boys with extra-ordinary power of the olfactory sense that they were able to smell out the truffle without the aid of a dog! (7) (8) (9). Several people have also been able to feel them under their bare feet or through thin shoes (10), (11). The dogs most suitable for truffle hunting are poodles, spaniels, and setters; but poodles were generally preferred, as they do not have a strong instinct or inclination for following game.

A detailed description of the truffle dog was given by the English sports writer John Henry Walsh in his The Dogs of The British Isles (5).

The truffle-dog is a small poodle (nearly a pure poodle), and weighing about 15lb. He is white, or black-and-white, or black, with the black mouth and under-lip of his race. He is a sharp, intelligent, quaint companion, and has the “homing” faculty of a pigeon. When sold to a new master he has been known to find his way home for sixty miles, and to have travelled the greater part of the way by night.

He is mute in his quest, and should be thoroughly broken from all game. These are essential qualities in a dog whose owner frequently hunts truffles at night – in the shrubberies of mansions protected by keepers and watchmen, who regard him with suspicion. In order to distinguish a black dog on these occasions, the hunter furnishes his animal with a white shirt, and occasionally also hunts him in a line.

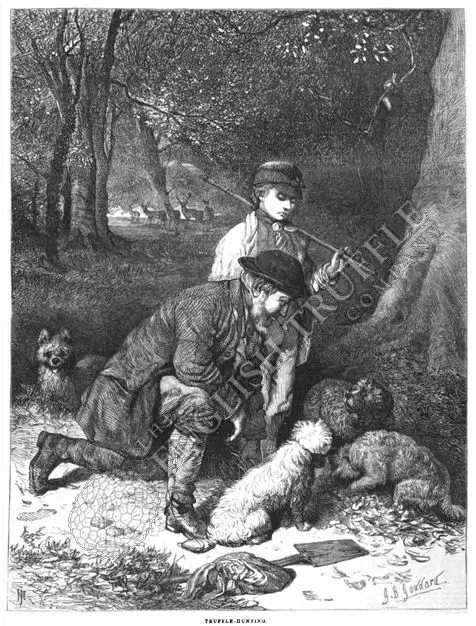

These dogs are rather longer on the leg than the true poodle, but have exquisite noses, and hunt close to the ground. On the scent of a truffle (especially in the morning or evening, when it gives out most smell), they show all the keenness of a spaniel, working their short-cropped tails, and feathering along the surface of the ground for from twenty to fifty yards. Arrived at the spot where the fungus lies buried, some two or three inches beneath the surface, they dig like a terrier at a rat’s hole, and the best of them, if let alone, will disinter the fungus and carry it to his master. It is not usual, however, to allow the dog to exhaust himself in this way, and the owner forks up the truffle and gives the dog his usual reward, a piece of bread or cheese; for this he looks, from long habit, with the keen glance of a Spanish gipsy.

Another observer of truffle hunting wrote:

Every time a truffle is found the dog stops and look at the pocket where the bread is, in a begging attitude, and do not begin to hunt again till after the “repay.” Food is doled out in the tiniest morsels, and yet before the day is over, though they still mechanically ask for the reward, they cease to eat it. They are the most tireless creatures imaginable. The assiduity of one in particular is extraordinary, I have seen her work from dawn until dark, collecting in that time nearly 8 pounds of truffles, and yet with as much briskness and apparent enjoyment for the last as for the first. (12)

The following is an extraordinary demonstration of the sense of smell that the truffle dog possesses:

In the summer of 1802, a gentleman walked with a person who is a professed truffle hunter: his dog found in the park at Amesbury, the seat of the Duke of Queensbury, many truffles; and as he continued his hunting, the dog, to the great surprise of the owner and the gentleman who accompanied him, suddenly leapt over the hedge which surrounded that part of the park, and ran with utmost precipitation across the field (which was the distance of at least 100 yards) to a hedge, opposite where, under a Beech tree, he found and bought in his mouth to his master, as the truffle dogs are taught to do, a truffle of uncommon size and which weighed 12 ounces and a half. (13)

Queen Victoria was given two white truffle dogs as a birthday gift by Prince Albert in 1842 (2).

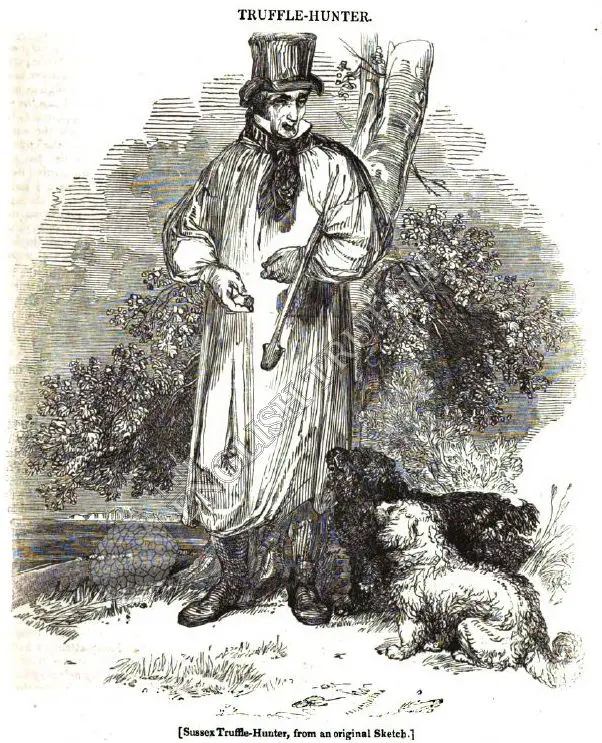

The Truffle Hunter

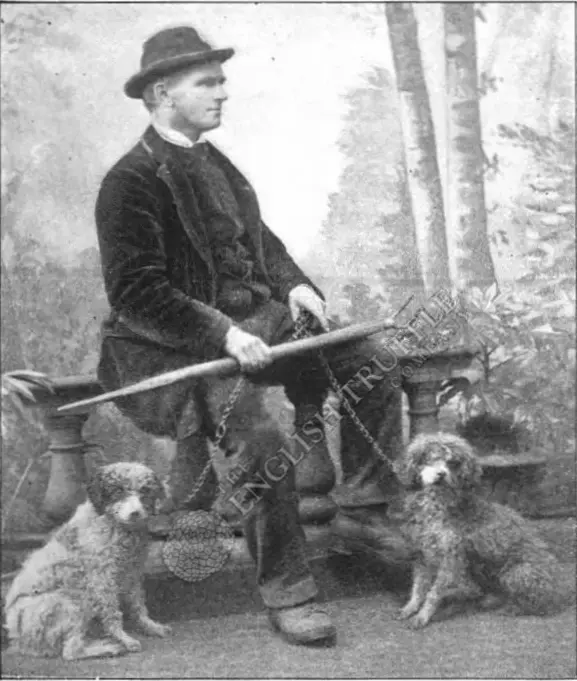

We meet a number of truffle hunters later on in the county accounts, but here learn a little of their equipment, clothing and work.

The truffle-hunter is set up in business when he possesses a good dog; all he requires besides will be a short staff, about 2ft. 5in. long, shod with a strong iron point, and at the other end furnished with a two-fanged iron hook. With this implement he can dig the largest truffle, or draw aside the briers or boughs in copse-wood to give his dog free scope to use his nose. (5)

Such a truffle spike can be seen in Salisbury Museum and in the photograph in the Wiltshire section below.

He wears a loose coat with pockets as voluminous as those of a poacher. One is reserved for truffles, and the other contains his modest lunch and a hunk of bread, with little scraps of which his companions will be rewarded. Two dogs are selected – one an experienced and clever veteran to do the work, the other a puppy in course of training. (12)

He travels frequently thirty or forty miles on his hunting expeditions; and with this (to use a business term) inexpensive “plant” keeps a wife and children easily. We know personally one blue grizzled dog of the old truffle breed which supports a family of ten children. (5)

Some of his excursions last a whole week, but early in the season the district within moderate walking distance, or easily reached by train, has not yet been overdone. (12)

Buying Truffles

English truffles were known to Mrs Beeton who included recipes for them in her 1861 Book of Household Management. She knew in which English counties they were to be found and of their soil and tree-host preferences. At this time, imported black winter (Périgord) truffles from parts of Italy and the south of France were sold both fresh and preserved. During the season, fresh truffles could be procured in Covent Garden market (13). Preserved truffles, usually immersed in oil and the air excluded, were sold in tins or bottles from shops like Fortnum and Mason’s and Crosse and Blackwell’s (8).

All was, however, not quite as it appeared. It is claimed (14), (4), (12) that consumers were being cheated. Rumours abounded that more than three-quarters of the truffles sold at Covent Garden in London were grown under Wiltshire beech trees. They went from village labourers through the hands of “wicked middlemen” and were sold as Périgord truffles. This was known to few. The public imagined that cheap English production must be inferior to expensive foreign one, so wholesale dealers sold then as a foreign importation at immense profit. The selling-price of the foreign luxury was from half a sovereign to 12 shillings 6 Pence per pound and of the home-grown, only a quarter as much. Clearly, there was no lack of temptation to defraud unsophisticated purchasers. Even experienced ones could be cheated. They knew the French truffle by its darker grain, but with an oil extracted from walnuts it was possible to deepen the grey of an English truffle till it closely resembles the other.

Wiltshire History

Introduction

The Wiltshire parish of Winterslow, near Salisbury, was famous for truffle hunting; it is sometimes described as “the headquarters of English truffling”. Truffle hunters worked out of the village from the late 17th century to the early 20th. At its peak, Winterslow was said to contain 10 – 12 truffle hunters. The occupation went in families. Yeates was the family that produced the greatest number of active truffle hunters, but the name Collins is more known with four generations of truffle hunters. The Collins family were at the centre of the truffle trade for 200 years. Eli Collins (1840-1924) was the most famous truffle hunter of the time, following his grandfather and father and his repute going beyond the borders of England. His son, Alfred (1869-1953), followed in the family tradition. They were, however, simply later practitioners of a rural profession that was centred on Winterslow for several centuries. It is claimed that the Collins family held the only Royal warrant to hunt for truffles in the UK until 1930 (15), though we have failed to find an official record of this.

There were no full-time truffle hunters, they undertook other jobs as well as tending their own ground. There was little regular, year-round agricultural work. There was, however, demand in the summer for farm labour – hoeing potatoes or turnips, binding corn-sheaves or building haystacks. At hoeing and harvest time men would work as farm labourers across the county staying away for the week and returning on Saturday night. Others would be woodsmen, making hazel hurdles for sheepfolds, spars for thatch or corn-ricks and hazel faggots (12).

Eli Collins

Eli Collins was born in 1840. He began truffle hunting at the age of 9 and carried on until he was 83. On the 1871 Census, he gives his occupation as “truffle hunter and hurdle maker”. He was ‘on the friendliest terms with almost every titled family in the truffle counties’ providing their sport. On the instruction of Lord Radnor of Longford Castle, Salisbury, Eli was given his famous velveteen coat. With his truffle hounds, Eli entertained the Earl’s guests, finding truffles beneath the trees of his estate.

Salisbury Museum has a testimonial certificate presented by The Earl of Radnor to Eli Collins in 1898:

Eli Collins has been allowed to hunt for truffles on my Estate for nearly 45 years, commencing to do so with his father – he has never during that time encroached in any way; and has conducted himself respectably. Aug 22, 1895.

Eli sent out regular parcels of truffles all over Britain, but he probably gave the landowners and local gentry first refusal. On one occasion Eli’s dogs found a truffle weighing more than 2lb (900g), which he presented to the then Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII. The Prince insisted on paying with a photograph of his mother, Queen Victoria, and a gold sovereign (1). This was not, however, his biggest; of this he said:

It was a foot round in size and so heavy that weighed 3 1/4 pounds (c. 1.5 kg). I sent it as a curiosity to gentlemen, and got something handsome; But I never were so proud as at finding he, and we calls ‘em the monster truffle to this day. (14)

There were downsides to the occupation too. An interviewer of Eli in 1863 wrote:

At one time I was almost tempted to drop the trade myself! What could be pleasanter than to wander through wood and playing with my dog friends for weeks together, and thus spend the bright autumn days. But unfortunately, one of my truffle friends knocked my daydream on the head by attributing his rheumatics to truffle hunting in damp and rain. “You see, Sir, the wetter it is, the better for our trade, though bad enough for we. Many and many a rainy week have I trudged on, wet up to the knees, followed by my little dog Nell”. (14)

Dogs

The truffle hounds used by the Winterslow men, though called terriers were said to be descendants of a Spanish breed that resembled the Barbet or small French poodle.

…she had an intelligent clever face, with bright black eyes, looking always at once, and sharp-pointed ears, always on the alert, and never quite one moment. The nose was sharp- pointed, and the whole face reminds me of the expression of a small quick terrier, only far more gentle and clever. I remarked on the clean-made limbs, and the long paws, which seemed made for scratching, and was assured of her strength and unwearied zeal in hunting for this peculiar kind of game. This dog was smooth-coated, white, with liver-coloured spots; but the generality have rather curly hair, a remnant of the poodle, from which these dogs are said to have been bred. (14)

There are different, sometimes overlapping accounts, as to how they first came to Wiltshire.

It is said that about two hundred years ago an old Spaniard brought two dogs into Wiltshire, and made a great deal of money by the sale of truffles which his dogs found for him; and at his death he left his money and his dogs to a farmer from whom he had received some kindness, and that the present dogs are derived from those he left the farmer (5).

This Spaniard was “ship-wrecked”, “came from the West Indies”, or according to others, “was a survivor from the Great Armada”.(16).

These versions are doubted by one writer:

Apart from other considerations, we may be permitted to doubt whether a Spaniard was a likely settler in an English village in Elizabethan times (1).

He suggested that the truffle dogs came from France during the eighteenth century, brought over by a local nobleman who is said to have been living in France when he succeeded to his English title.

The real story, however, comes from Eli, ending with the assertion that it must be true:

cos my grandfather had told it to my father and my father over and over again to me, and as we knows the dogs must be Spanish.

It was in my grandfather’s time that a furriner [foreigner] came to these parts with several dogs, couldn’t speak English, and bided in one of our farmer’s barns down there. Soon he began to hunt for truffles, and after a bit, when he had picked up English, told our folks he was Spanish, and his dogs, too, and taught my grandfather and others to hunt for ‘em. He made a power of money, and they do say left it to the farmer in whose barn he slept and that’s how farmer B______ got his riches. How that may be, I can’t say, but certain he left his dogs to grandfather and I, and that’s how we got the breed and learned truffle hunting, for before that nothing was known about ‘em or where they growed. (14)

Dog Tax

After France declared war on England in 1793, more revenue was needed and William Pitt, the then Chancellor, imposed a range of taxes, including a tax on owning dogs in 1796. Under the bill, all people who kept dogs that could be used for sport, as well as those who owned two or more dogs, were charged five shillings per dog (17), (18). This amount increased to 12 shillings a year. The truffle hunters including Eli wanted the dog tax reduced:

You see Sir, I speaks more for the others than for myself, but even I am forced to give up all my dogs but one, and she can’t find out alone the same quantity of truffles. There’s no chance of our poaching with them, as was said, for that have no nose for anything else, and are too small and weak for any game. You come with me and see a truffle hunt, and you soon say that they are a separate breed, just fit for truffling, and nothing else. (14)

Eli described the grievance which weighed heavy on these poor labourers. He drew up a petition against the tax, which was presented to parliament in 1860 by the late Lord Herbert, though without effect.

We, the undersigned Poor Men of the parish of Winterslow, in the county of Wilts, do humbly solicit the attention of your honourable house to our humble petition.

Being poor labouring men, mostly with families and aged, and living in a woody district of the County, where there is a great many English truffles grow, which we cannot find without dogs, we do therefore keep and use a small pudle [sic] sort of dog, wholly and solely for that and no other; And, as it is in the winter season of the year when we gather them, when labourers is generally on the excess in our neighbourhood, we often are enabled by the aforesaid dogs to provide a subsistence for our families, otherwise we should often be a burden to the parish, and it hath being carried on by ancestors for generations without paying any tax for the dogs; But as the taxes now levied upon us – viz. 12 shillings per year, and as we have to keep our dogs six months when we have no use for them, it presses so heavy upon us, that without redress we shall in most cases be obliged to make a sacrifice of our dogs, and thereby become a burden on the parish, and in some cases paupers on the Union.

and, as it did please your honourable House in its wisdom to exempt dogs used purposely for cattle for the maintenance of shepherds, etc., from paying of tax, we do humbly beg your honourable house we’ll take our case into your kind consideration, and exempt us from paying tax on a truffle dogs; That we may be enabled to follow our avocation for our own families subsistence. And your petitioners will forever pray, etc.

Some claim the dog tax levy heralded the death knell for truffle hunting which gradually declined into an occupation which did not pay (2).

Recollections of Eli Collins

In response to an article on English Truffles in The Times in 1938, there were many letters from readers. Several have recollections of Eli.

About 45 or 50 years ago (c. 1889-1894) – my brothers and sisters and I used often to go with Eli Collins and his dogs when hunting for truffles in my father’s beechwoods near Salisbury where Collins had leave to hunt. The dogs were small rough head of a sort of terrier breed as I remember them and found the truffles by sensing about and then scratching where they smelt them when Collins would dig with his short iron shod stick and find them. They were generally about the size of a hen’s egg or a golf ball. The dogs were always rewarded. We had two dogs which we taught to find truffles. One was a very curly coated retriever and the other a terrier of sorts that must have been related to a bulldog. Both found truffles but they soon got tired as they were more interested in game but they found, in about an hour, about a pound which we ate stewed. Eli Collins charged my parents 2 shillings a pound for truffles found in our woods and I think 5 shillings to other people. (19)

A truffle hunter called Eli Collins came often to Wilbury from Winterborne with his little dogs, who scratched under the beech trees and found delicious dark brown truffles. (20)

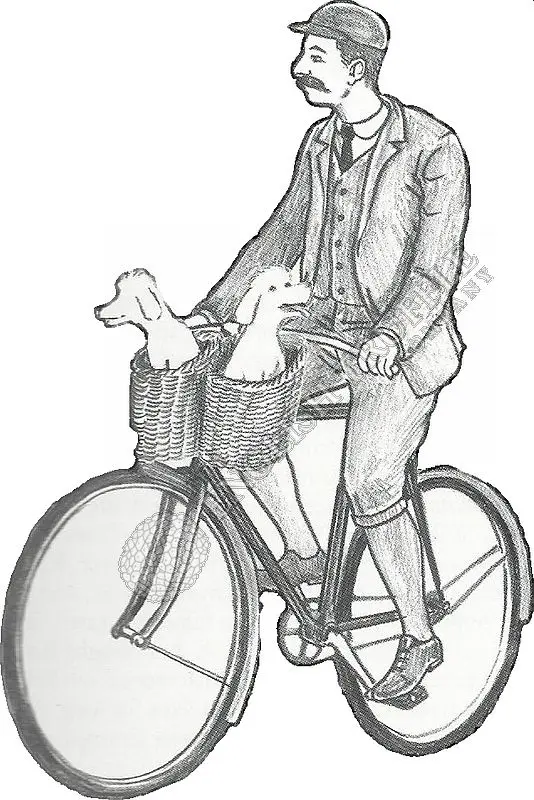

Alfred Collins

Eli’s son, Alfred, born in 1869, continued the family tradition of truffle hunting. He too gave his occupation in the census as “Truffle hunter and hurdle maker”. Alfred used two poodles. If hunting within 20 miles of his home, he went by a bicycle, carrying one dog in a special leather bag (or wicker basket on his handlebars in other sources) while the other ran, changing them over every 5 miles. Both were carried home however after a tiring day’s work. His star truffle dog was Major; who had a passion for truffles and could eat as fast as he could uncover them!

On a good day, Alfred could collect 25lbs, but on other days he found none. In the early 1920s, truffles fetched 2s 6d per pound, by retirement, he could get 5s 6d per pound. Truffles were primarily sold to private customers. They were always posted off as soon as possible in shoe boxes, which the children collected from the boot maker for a penny each. Any not dispatched were eaten by children on bread and butter. (21)

Alfred carried on this profession until with rheumatism prevented him from continuing, retiring in the 1930s. He died in 1953 a poor man and was known as “the last professional truffle hunter”.

In 1974, Alfred’s children appeared in an episode of a television series called A Taste of Britain. Hosted by Derek Cooper, the programme set out to document traditional foods and food practices in Britain before they disappeared. It included truffle hunting and interviewed them. They wished their father had passed on his methods and skills to them. A view echoed by Alfred’s grandson, Victor, interviewed in 2006, who could not understand why his grandfather, chose to take his knowledge to the grave (22). Mr Collins has never tasted truffle, despite his family being at the centre of the trade for over 200 years. All that remains of the business are a set of 80-year-old truffles in a tobacco tin.

We could never understand why Grandpa Collins said he wanted the trade to die with him. It was selfish really. We could have been millionaires by now,” said Mr Collins, a former seaman, woodworker and lorry driver who lives near the family’s home village of Winterslow, Wilts.

One of the letters to The Times in 1938 includes recollection of Alfred:

Sir, – I have read with much interest your Correspondent’s article of truffles and venture to reply to it, having some experience on the subject.

Ever since I was a small child at my old home in Wilts, my sister and I, taught by an old gardener, found truffles with and without a truffle dog, both above and below the ground. Now truffle hunting it seems is a lost art, so far as dogs are concerned, for, some years ago, I saw the last of the breed, a dog then 11 years old belonging (I believe) to a son of Eli Collins. The latter used to supply us with our dogs…

The market price of our English truffles (quite a different article to the French ones being black with grey insides) was before the war 20 shillings a pound, so I was informed by a friend of mine who paid that. (23)

Sussex History

Sussex was another county known for its truffles. The beechwoods of the South Downs including, in the Arundel district, were frequented by truffle hunters between 1795 and 1908. Some of these were shepherds using their sheep dogs (8).

The old man represented in the cut, who is a celebrated trainer of truffle dogs, generally keeps a few truffles either dried or soaked in grease through the winter, thus preserving in some degree the older, to serve for teaching the young dogs.

Those proprietors who are game preservers are generally unwilling to let the truffle-hunters into their grounds, as they are sometimes tempted to change the object of this search and follow other game; the old man of whom we have given a sketch was sent for to an estate in Sussex for the purpose of explaining the mode of training the dog and exhibiting the manner of hunting: his good character has obtained him permission to range through the woods over consider a range of country in the neighbourhood (13).

One of the earliest accounts of truffle hunters in Sussex is by TW Horsfield. In the second volume of his History of Sussex (1835) says of the parish of Patching:

The beech woods in this parish and its immediate neighbourhood are very productive of the truffle. About 40 years ago [i.e. c. 1795] William Leach[*] came from the West Indies with some hogs accustomed to hunt for truffles and proceeding along the coast from Land’s End in Cornwall to the mouth of the River Thames determined to fix on that spot where he found the most abundant stop he took four years to try the experiment, and at length settled in this parish where he carried on business of truffle hunter till his death. (24)

[*Same family name as at Cheriton in Hampshire (below)].

A little later, around 1880, an old Irish Woman who lived in Patching, truffle hunted under beech trees on the local downland. She never divulged where she had found them and the secret went to the grave with her.

In another of the letters in response to the 1938 article on English truffles in The Times, The editor of the Sussex County Magazine wrote:

Some 30 years ago (c. 1908) when I introduced myself in the subject of truffle hunting sufficiently to make enquiries, I’ve found that pigs have been used both in Sussex and Kent up to a few years of my inquiry the though most of the local truffle hunters use dogs. the pig would devour the truffle: the dog would not. So strong is the aroma of this esculent fungus that I have even heard the man who relied upon his own sense of smell to discover truffles lying just below the surface of the ground. Most of the truffles hunted in Sussex were found in the beech woods and half a century ago truffle hunting was almost an industry but has now died out. The last truffle hunter I met was in a beech wood near Trayford [now Treyford], West Sussex about 1908. He had a dog and carried a pointed stick for turning the loose earth (25).

This parish of Patching was also responsible for a truffle dish of the time, the “Patching truffle pie”. This contained veal, fat ham, lean ham, goose livers and shallot, topped with sliced truffles and a pastry lid and then baked. When it was about to be served, the lid was lifted, and a glass of madeira poured in. By 1936, truffles were no longer found near Patching (26).

Truffle hunting in Sussex also appeared in fiction. Rudyard Kipling wrote a story “Teem— a Treasure-Hunter” (first published in 1935). A synopsis of the story is given by the Kipling Society:

Teem, a little French dog, … has the gift of sniffing out truffles, … and indicating their whereabouts to his master, who digs them up for sale. He sells Teem to an Englishman, … who is later involved in a car-accident whereby the dog escapes.

He is adopted by a charcoal-burner who does not recognise the truffles which the dog brings him and whose daughter is suffering from consumption. … Teem finds more truffles which he takes to the local landowner, who recognises and buys them from the charcoal-burner.

With the money from the truffles, the father is able to obtain medical attention for the girl …. The story ends with the patient beginning to recover from her complaint and her father, with the aid of the dog, operating a successful truffle-hunting business.

Hampshire History

Observations are made of truffle hunters in Hampshire between the late 18th and 19th centuries. Accounts and the range of dates show again it was a family occupation passed from father to son. The locations suggest at least two truffle hunting families.

Gilbert White (1720 –1793) was a “parson-naturalist”, a pioneering English naturalist, ecologist and ornithologist. In his Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne (1789), he mentions truffle hunters on several occasions. His brother, Henry, lived at Fyfield near Andover and had a truffle hunter visiting his grove of beech trees between 1770 – 1790. Gilbert too had one or two truffle hunters, with their two little “cur-dogs” (mongrels), look in his hedges and nearby areas between 1775 – 1791. One of these was from Holiburne (now Holybourne) near Alton (27).

Writing around 100 years after Gilbert White observed truffle hunters at Selborne, James Edmund Harting wrote:

During many rambles in the neighbourhood of Selborne in summer and autumn, I never chance to meet with or hear of any professional truffle hunter of the old sort, and it would seem as if the race must have died out. It is possible, however, that a truffle hunter who may be heard of at the present time at the Golden Pot, Shaldon, near Alton, and who still plies his avocation in that neighbourhood, maybe a descendant of “the Holybourne truffler” referred to by Gilbert White, since he informed the friend of the writer that both his father and his grandfather had both been truffle hunters in the county before him. (28).

Amongst responses to questions about English truffles asked in the periodical Notes and Queries in September 1864 was one from Hampshire:

Truffles are plentiful occasionally in Hampshire. In the village of Cheriton, about 3 miles south of Alresford, when I was a boy, there were two families whose principal means of support depends upon the success of their truffle-hunting; and, remarkable enough their name – like that of the man said by Mr M. A. Lower to come from the West Indies, was Leach[*]. At present there are three brothers in the village who follow the occupation of their sire. These men do not, as your correspondences bribe the dogs by giving them meat to prevent their eating the luxury, but they give them a piece of bread now and then as a reward for their discoveries. Nor do the dogs, as might be inferred from the communication, get possession of the truffles. They find them, and their master digs them up with a pike he carries on purpose. The dogs used by these men are white ones, very similar to the French poodle. The hunting is not limited to any particular places; but in all the hedgerows round and fir plantations are the truffles found (29).

[*M. A. Lower – A Compendious History of Sussex,1870. For further reference to a man by the name of Leach, see the Sussex section].

A customer of this family wrote to The Times in 1938; one of many letters about English truffles in response to an article on them.

When, as a young bride, I came to my husband’s home, Hinton Ampner House, Alresford in 1888, there lived an old man living in the nearby village of Cheriton who possessed a truffle dog, which used to find truffles under beech trees in Tichborne Park, adjoining Cheriton village. The old man used to call upon us, bringing a red handkerchief filled with glorious truffles (30).

Another correspondent wrote:

As a boy I lived a Crawley Court in Hampshire and well remember meeting old Eli Collins with three or four small brown and white, unclipped poodles hunting for truffles along the beech belt which bordered one side of our estate. … I might add that the dogs could wind the truffle from considerable distances, and we had hurry, as they sometimes ate the small ones (31).

A third letter writer too had witnessed truffle hunting in Hampshire, this time in around 1819. The location may mean this is another sighting of a descendant of “the Holybourne truffler”:

About 60 years ago when I was a child, I often watched an old man hunting for truffles in Hackwood park, near Basingstoke. The part of the park in which he worked was generally between the Mansion and the Windslade Road where the drive is (or was) bordered by woodland. The method was that a trained dog in this case a small mongrel with affinity to a spaniel – nosed about in the spinney till he marked a spot like a pointer marking game. The old man then dug at the spot indicated with a stout two-pronged fork on a short handle and if the truffles was found, gave a fragment of biscuit to the dog and set him off on a further hunt. The truffles were small black tubers of irregular shape, the largest being about the size of Walnut. As far as my memory carries me, the tubers appear to be plentiful and the bag the old man carried soon filled up. The old truffle hunter told us that trained pigs were often used for the business as well as trained dogs (32).

The below too, written in 1920, may relate to the same man:

In some counties, but not so far as I am aware in Worcestershire, one of the harmless snappers up of unconsidered trifles is the truffle-hunter. At Alton, in Hampshire, one of these men appeared in summer; he carried an implement like a short-handled thistle spud, but with a much longer blade, similar to that of a small spade but narrower; he was accompanied by a frisky little Frenchified dog, unlike any dog one commonly sees, and very alert. The hunting ground was beneath the overhanging branches of beech-trees, growing on a chalky soil; the man encouraged the dog by voice to hunt the surface of the land regularly over; when the dog scented the truffles underneath, he began to scratch, whereupon the implement came into use, and they were soon secured. I have since been sorry that I did not interview this truffle-hunter as to his methods and as to his dog, for I believe he is no longer to be seen in his old haunts (33).

Why Did Truffle Hunting Almost Die Out?

Although Alfred Collins retired in the 1930s, the decline had been going on for much longer.

1876 – “the attempt has almost died out in England.” (8)

1883 – “but the old race of truffle hunters seems to have almost, if not entirely, died out.” (13)

Overseas Parallels

Some of the potential reasons for this decline can be found by looking overseas. Recognising that we are talking about a different truffle, the black winter or Périgord truffle (Tuber melanosporum), parallels may be found. In France, Black truffle production has fallen spectacularly, from around 1000 tonnes per year around 1900 to around 10 – 50 tonnes today. The reasons for this decline are generally thought to be:

- Loss of some of the truffle hunters / their local knowledge in the trenches of World War I (34), (35).

- A migration of people from rural to urban areas. Leading to the near ending of activities that had kept woods half clear and them becoming more wild / overgrown:

- firewood cutting.

- charcoal production.

- forest grazing by flocks of sheep.

Italy adds deforestation to this list. In Spain, there was a collapse in truffle production in the 1970s, explained again by rural depopulation and the collapse of many traditional forest uses, in addition to reforestation with conifers.

Habitat Loss

Loss of habitat in which any species grows, fungi or other, is often given as a reason for reduction in their numbers. In the case of English truffles, habitat losses are cited:

- Felling of the woods including ancient woodland, primarily to agriculture and forestry, with small amounts to housing, roads and industry. (35),(36)

- Modern farming methods (intensified cultivation and mechanisation etc). (36)

We can too probably add deforestation and reforestation with conifers.

Truffle hunting in England, was largely in newer, not ancient woods which are greater than 400 years old. It was principally undertaken in plantations of beech or beech and fir (pine). Beech was widely planted throughout Britain during the 18th and 19th centuries (37). Taking 1800 as a midpoint, today these trees would be over 220 years old. In 1930, when Alfred Collins retired, they would have been 130. In a truffle plantation situation, where inoculated trees are specifically planted to grow truffles, indicative figures for the longevity of truffle production are over a century for oak and over 50 years for hazel. Figures for the longevity of natural growing truffles on beech are not known, but it is thought that truffle occurrence in beech woods of this age would have declined or even disappeared.

We have searched in vain for truffles in beech woods that were known to have them in Eli Collins’ era. Many have gained large amounts of ash and sycamore whose abundant seedlings can tolerate the deep shade of the beech trees. The truffles fungus does not grow on the roots of either of these two species.

In England, coppicing was a widespread method of woodland management. One part of the wood, a “coupe”, was harvested each year. Coppice trees respond to cutting by sending up multiple stems. Woodsmen, such as Eli and Alfred Collins, used these for making sheep hurdles and other products, or for making charcoal for industry such as iron-making. The 20th century saw a marked decline in coppicing, without it, a dense canopy of taller trees develops, shading out any undergrowth and the woodland floor, probably leading to a reduction in the number of truffles.

Financial Reasons

Truffle hunting was (and is) hard work and “...it is a very uncertain calling, and the truffle hunter does not amass riches. He has many a bad season and blank day.” (12). Years that have low amounts of rainfall result in a poor harvest of wild truffles.

The Dog Tax levy was blamed for heralding the industry’s decline with hunters keeping just one dog rather than 3 or 4. While direct sales made the truffle hunter a better price than selling to middlemen, it did not pay well. A truffle hunter might get the equivalent of only 12- 20p per pound (c. 450g) (38). With reduced demand, truffle prices fell during the First World War to all-time lows. Demand did not recover in the difficult post war years. (39)

Overseas Truffles

Even in the late 19th Century, competition for the English truffle hunters from abroad was recognised:

…moreover, the large supply of truffles in the English market from foreign sources, especially from parts of Italy and the South of France, must render the English truffle hunter’s occupation much more precarious and less remunerative than was formerly the case. (28)

Access to Woods

Having permission to go into suitable woodland looking for truffles was an issue then (and now).

The best grounds are where the earth has been trenched or moved-that is, in gentleman’s parks, pleasure-grounds, avenues, and preserves. It would be unreasonable to expect the privilege of visiting these to be freely extended to an unlimited number of applicants. Moreover, it often happens that the owner, after seeing the men at work, become so enamoured of the sport that he buys a dog, and reserves the best ground for his own amusement and that of his friends. (12)

The main reason then, and now, is that the truffle and shooting seasons coincide and that landowners do not want their game disturbed or taken:

There are probably at the present day, few owners of woods and plantations who would care to have their coverts disturbed by truffle hunters in the height of the shooting season. However the latter might vouch for the steadiness of their dogs and their total disregard of game. (28)

Those proprietors who are game preservers are generally unwilling to let the truffle hunters into their grounds, as they are sometimes tempted to change the object of search and follow other game. (13)

But the calling is in general discountenanced by the landowners, as it leads to trespassing, vagrant habits, and a look-out for higher game. (7)

Modern Times – The Re-birth of the English Truffle Industry

After the retirement of Alfred Collins, truffle hunting virtually disappeared. It was still, however, occurring among a handful of individuals:

- Marwood Yeatman writing on English regional food, cites a Sussex source still selling English truffles in the late 1950s – “An old man brought them up from the country every season, then failed to reappear, and the line went dead.” (40)

- Derek Cooper’s 1974, television series “A Taste of Britain” mentioned earlier, included truffle hunting, During recording for BBC Radio 4’s The Food Programme in 2014, I was shown clips of this programme, though don’t know where or when they were filmed but it was in England.

- An acquaintance knew friends that truffle hunted on Cranborne Chase (Dorset / Wiltshire border) in the 1970s.

- A friend remembers being taken truffle hunting in West Dorset as a child in c. 1981.

“Accidental” truffle finds were also being made, some making it into the media. A few examples:

- In 2002, a Gloucestershire man reported that squirrels had been digging up truffles in his garden for 6 years (41).

- In 2004, a puppy belonging to a celebrity chef found a truffle when out for a walk in Hertfordshire (42).

- Also, in 2004, a farmer discovered about 10 kilograms of summer truffles on the Wiltshire/ Berkshire border (43).

- In 2007, I was in a Wiltshire pub, when a regular brought in a carrier bag of truffles. They came from under his hedge and were exchanged for his bar bill for the next few months!

- In 2008, a gardener found 10 truffles in a garden in Plymouth (44).

- Also, in 2008, schoolchildren near Swindon found 10 truffles in the school vegetable patch (45).

The third example is worth exploring in a little more detail. In 1990, an arable farmer on chalk planted 10 acres of beech, hazel and other trees under a Government-funded farm woodland scheme. 15 years later his wife found these “black things a badger had dug up” while walking through it. An initial 10 kilograms were taken to nearby restaurant where they were identified as summer truffles and purchased. The chef / proprietor called in fungi expert Roger Phillips, who examined the find and sent a sample to Kew Gardens to be classified, categorised and recorded. He said: “We have not seen truffles in this sort of quantity in the UK in last 60 years.” (52). In 2008/9 the farmer expected to harvest 200-300kg claimed to be “the largest truffle hoard recorded in the UK”. Today this wood forms part of a thriving truffle business supplying many leading restaurants. The secret location has regularly appeared on television and in the media.

One of its early visitors was Somerset-based truffle hunter Tom Lywood, who has also regularly appeared in the media with his Lagotto truffle dogs. He even gave a TEDX talk on truffle hunting once. Tom is estimated to be one of around a dozen truffle hunters in England today.

To try to meet some of the huge reduction in truffle harvests in their natural areas of mainland Europe, a lot of focus was on developing cultivation techniques. In the late 1970s, the French developed techniques to establish successful truffle plantations. These spread to Spain and Italy, and later into many other countries. In the late 90s, Truffle UK was set up encouraging British farmers to establish truffle orchards through planting inoculated trees. Hot on their heels, was Dr Paul Thomas. With his company Mycorrhizal Systems, he appeared on the BBC television programme Dragon’s Den. Both companies have had successes. In 2011, summer truffles were found in a recently planted woodland in southern England that had been inoculated with seedlings supplied by Truffle UK. In Leicestershire in March 2015, Paul’s company grew summer truffles. Black winter (Périgord) truffles have now been grown in the UK including by the Duke of Edinburgh and a truffle farmer in South Wales. Today, quite a number of landowners including even Asda (55) and later Waitrose (56) have established truffle orchards in all parts of the UK.

Successful truffle orchards need truffle hounds to search in them. Paul Thomas partnered with Marion Dean to establish a truffle dog training school for orchard owners and potential truffle hunters. This too captured the media’s attention. In 2008, I attended the school with my Labrador for a training session. Three months later we participated in and won the country’s first truffle hunting championships beating 30 other competitors. Several camera crews filmed this for news and documentary programmes. Another of my fellow competitors, Melissa Waddingham, has also established a business based on English truffles.

In 2011, Marion wrote Discovering the Great British Truffle: Nature’s Best Kept Secret Brought to Life for the Contemporary Kitchen covering her experiences and the preparation, cooking and sourcing of truffles.

Truffle finds are becoming more common. Since 2014, we have received over 40 reports of them being found in gardens. Finds peaked during the first Covid-19 lockdown in spring 2020, when garden tidying discovered hitherto hidden, and sadly unripe, truffles.

With extensive media attention and growing awareness that there were and are truffles in England, businesses have been established in addition to those growing / selling truffle trees and offering dog training. Several companies, including the one mentioned above, now sell English truffles, both wild and orchard grown. These companies supply discerning consumers and the restaurant trade, with many Michelin starred and other establishments now serving English truffles. They are today also used by food manufacturers, both large companies and small artisan producers, in products such as oils and honey, They have appeared in prize-winning dishes, chef competitions and in 2020 were included in the dinner for the BAFTA awards. People interested in food and / or dogs can go on truffle hunting “tours” / experiences without leaving the country and there are also individuals that can be hired to visit your woods or orchard to search for truffles. From “near-death” in the 1930s, through re-birth around the millennium, the future is bright for English truffles.

References

- Whitlock, Ralph. Start of the season for hunting the truffle. The Times. 15 October, 1966.

- Davis, Julie. Truffles – what a rare treat indeed! WSHC Blog. [Online] Wiltshire & Swindon History Centre, 07 January 2014. https://www.wshc.org.uk/blog/item/truffles-%E2%80%93-what-a-rare-treat-indeed.html.

- Robinson, Tancred. An account of the tubera terræ, or truffles found at Rushton in Northamptonshire; with some remarks thereon. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 1693, Vol. 17, pp. 824-826.

- Broome, CE. Notes on Truffles and Truffle Culture. The Journal of The Royal Horticultural Society of London. 1866, Vol. 1, pp. 15-21.

- Walsh, JH. The Dogs Of The British Islands. n.p. : Horace Cox, 1882.

- English Heritage. Georgians: Parks and Gardens. [Online] https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/learn/story-of-england/georgians/landscape/.

- Anonymous. Truffles and Truffle Hunting. The Leisure hour; an illustrated magazine for home reading. 505, 1861, pp. 549-551.

- —. Truffles. All the year round. 1876, Vol. 14, 381, pp. 52-56.

- —. Truffle Hunting. Illustrated London News. 1559, 1869, Vol. LV, p. 325.

- “Terrière, Mrs La”. Letter. The Times. January, 1939.

- Moore, Victoria. Boy claims amazing ability at finding truffles with his feet. Daily Mail Online. [Online] 08 August 2007. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-474144/Boy-claims-amazing-ability-finding-truffles-feet.html.

- Graham, P. Anderson. Truffle Hunting in Wiltshire. Longman’s Magazine. 1895, Vol. XXV, CXLIX, pp. 531-539.

- Anonymous. Truffle Hunter. The Penny Magazine of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. 1838, Vol. VII, 381, pp. 89-90.

- J.L. Truffles and Truffle Hunting. Once a Week: An Illustrated Miscellany of Literature, Art, Science & Popular Information. 1863, Vol. IX, 220, pp. 317-321.

- Williams, Rebecca. From ground to plate – the story of a summer truffle. Hold The Anchovies Please. [Online] https://www.holdtheanchoviesplease.com/summertrufflerecipe/.

- Anonymous. Truffles to seek: a subterranean harvest. The Times. 22 December, 1938, p. 15.

- Major, Sarah Murden and Joanne. The taxing of dogs in the eighteenth century. All Things Georgian. [Online] 21 February 2019. https://georgianera.wordpress.com/2019/02/21/the-taxing-of-dogs-in-the-eighteenth-century/.

- Elliot, Grace. A Tax on Dogs . English Historical Fiction Authors Blog. [Online] 27 July 2013. https://englishhistoryauthors.blogspot.com/2013/07/a-tax-on-dogs.html.

- Pinckney, Alice M. Letter. The Times. 7 January, 1939, p. 8.

- Bailey, Mrs J. D. Bonnet-shopping in Jermyn Street. The Times. July 20, 1960.

- Manners, J.E. Truffle Hunting in England. Country Life. 7 January, 1971.

- The Daily Telegraph. Unearthing the lost secrets of truffle hunting. [Online] 09 September 2006. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/1528422/Unearthing-the-lost-secrets-of-truffle-hunting.html.

- Byng, Lady Eleanor. Letter. The Times. 31 December, 1938, p. 8.

- Horsfield, TW. The History, Antiquities and topography of the County of Sussex, second volume. Lewis : Sussex Press, 1835.

- Beckett, Arthur. Letter. The Times. 5 January, 1939, p. 8.

- Chambers, Admiral CB. Gastronomic Sussex. The Sussex County Magazine. 1946, Vol. 10.

- White, Rev Gilbert. The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne. London : White, Cochrane and Co., 1789.

- Harting, James Edmund. Essays on Sport and Natural History. London : Horace Cox, 1883.

- Batchelor, J. W. Letter – Truffles. Notes and Queries. 1865, Vols. s3-VII, 170, p. 265.

- Steen, James. The Foodie: Curiosities, Stories and Expert Tips from the Culinary World. United Kingdom : Icon Books Limited, 2015.

- Kennard, CH. Letter – Truffles. The Times. 2 January, 1939, p. 10.

- Cooksey, Reverend. Letter – Truffles. The Times. 2 January, 1939, p. 10.

- Savory, Arthur H. Grain and Chaff from an English Manor. Oxford : Basil Blackwell, 1920.

- Hughes, Pascale. What’s it like to be a professional truffle hunter? inews.co.uk. [Online] 8 March 2019. https://inews.co.uk/inews-lifestyle/work/zak-frost-professional-truffle-hunter-262050.

- Bailey, Dr Sue. A truffle for Christmas? Cambridge Edition. [Online] 18 December 2019. https://cambsedition.co.uk/?food-drink=a-truffle-for-christmas.

- Become a company. The re-birth of the British truffle industry? [Online] 19 March 2015. https://blog.becomeacompany.co.uk/re-birth-british-truffle-industry/.

- The Conservation Volunteers. The planting of woodland. Conservation Handbooks. [Online] 2002. https://www.conservationhandbooks.com/woodlands/a-brief-history-of-woodlands-in-britain/the-planting-of-woodland/.

- Marren, Peter. Mushrooms: The Natural and Human World of British Fungi. n.p., United Kingdom : Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018.

- Hall, Ian R, Brown, Gordon T. & Zambonelli, Alessandra. Taming the Truffle: The History, Lore, and Science of the Ultimate Mushroom. n.p. : Timber Press, 2008.

- Yeatman, M. The Last Food of England: English Food : Its Past, Present and Future. United Kingdom : Ebury Press, 2007.

- Stroud News & Journal. Squirrels lead to garden treasure. [Online] 4 September 2002. https://www.stroudnewsandjournal.co.uk/news/6701289.squirrels-lead-to-garden-treasure/.

- BBC News. Puppy’s truffle find stuns chef. [Online] 29 January 2004. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/beds/bucks/herts/3441537.stm.

- —. Truffles batch ‘a huge discovery’. [Online] 18 September 2004. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/berkshire/3668228.stm.

- —. Truffles surprise for gardener. [Online] 6 August 2008. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/devon/7545726.stm.

- Hilley, Sarah. Pupils unearth a gourmet delicacy. Swindon Advertiser. [Online] 19 October 2008. https://www.swindonadvertiser.co.uk/news/3769707.pupils-unearth-a-gourmet-delicacy/.

- BBC News. Yorkshire bid for truffle centre. [Online] 25 November 2007. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/west_yorkshire/7078904.stm.

- Waitrose & Partners. Waitrose & Partners Plants its Own Truffle Tree Orchard in Supermarket First. Waitrose Press Area. [Online] 25 April 2019. https://waitrose.pressarea.com/pressrelease/details/78/NEWS_13/10997

- Collett-Sandars, W. Truffles. The Gentlemen’s Magazine. 1877, Vol. CCLXI, pp. 726-739.

- Britten, James. Popular British Fungi. London : The Bazaar, 1877.

- “A la Terriere”. Truffles and Truffle Dogs. Country Life. August 24th., 1907.

- Bathurst, The Hon. Ben. Letter. The Times. January, 1939.

- Williams, John. Truffles. Journal of horticulture, cottage gardener and country gentleman. 528, 1880, Vol. XXI Third Series, p. 177.

- Bolton, Rev. James. Children’s Address. Church of England Sunday School Monthly Magazine for Teachers. November, 1860, p. 384.

- Potter, Rev. Prof. MC. Letter. The Times. 4 January, 1939, p. 6.

- Anonymous. Truffle Dogs. The Times. 9 January, 1939, p. 18.

- —. Truffles. Journal of horticulture, cottage gardener and home farmer. 528, 1890, Vol. XXI Third Series, pp. 177-178.

- —. The Domestic Service Guide. London : Lockwood and Co., 1865.